Water discovery could change the nature of future Mars exploration

The claim that flowing water has been discovered on Mars could undoubtedly enhance knowledge of the Red Planet, a scientist from Plymouth University has said.

But it could also make future exploration of the planet more difficult because of restrictions designed to prevent the contamination of any potential biological material or ecosystem on Mars, or anywhere throughout the solar system and beyond.

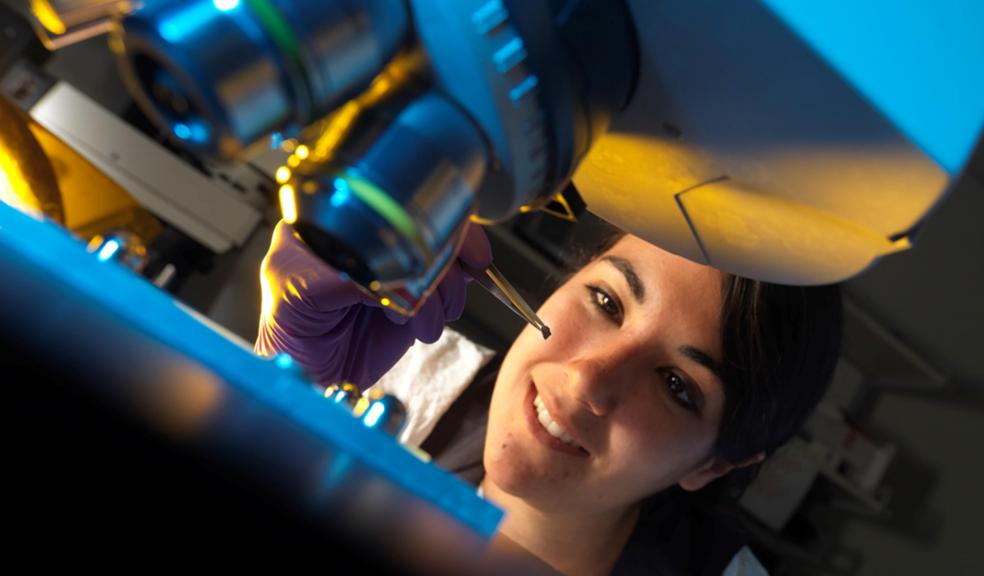

Dr Natasha Stephen, Scientific Officer in the Plymouth Electron Microscopy Centre, has spent the past six years analysing Martian meteorites and satellite and rover data about one of our nearest planetary neighbours.

And she believes the possible presence of water, as revealed by NASA scientists this week, provides an exciting new insight into the long-asked question of whether there could be life on Mars.

“This new announcement does not confirm the presence of water itself, but the best evidence we have that has been observed directly, over time, changing with the Martian seasons. It is not a claim for life on Mars, just further evidence that there could be the potential for extant life on the Red Planet that we haven’t found yet,” said Dr Stephen, also an associated lecturer within the School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences.

“These identified areas will now be classified as ‘special regions’ and protected by the United Nations Outer Space Treaty. So whilst they technically can’t be confirmed until we’ve actually visited them, they will now be off-limits to both robotic and human exploration, meaning we will have to continue to explore these areas remotely from orbit.”

Dr Stephen is one of few geologists using multiple different techniques to analyse Martian meteorites, and is building a database of in-depth and complex information with respect to their chemical and mineralogical composition.

When new samples are received at Plymouth University, they are initially categorised in terms of their petrology – their detailed mineralogical make-up – before further tests establish whether they likely solidified on the planet’s surface or at depth.

The research then focusses on whether the meteorites formed on the surface from a volcanic eruption, or if they may have been ejected from below the Martian surface at some point in Mars’ ~4.6 billion year history.

Using the state-of-the-art equipment within the Electron Microscopy Centre, she is also able to generate magnified images of the rocks, making it possible to catalogue the precise physical structure of each specimen.

Dr Stephen said: “The main goal of my work is actually to establish what happened to the planet and whether it might occur on Earth in the future. Around 45,000 meteorites that have fallen to Earth have been collected and recorded, but just 155 of those recorded are presently known to have come from Mars. They – along with the information generated by two Rovers on the surface of Mars and several orbiters generating a huge amount of remote data – are providing the only clues we have to the fate of Mars.”